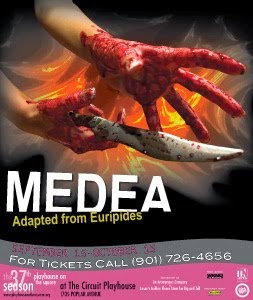

Recently, a friend suggested that I write about the didactic function of ancient Greek Tragedy. This is easier said than done*. However, since Greek tragedy is still performed today, 2,400 years after its birth, it must have something profound to say to modern audiences.

With the assumption that this enduring influence must be, at least in part, didactic, and with the knowledge that I want to focus on something rather than everything or nothing I decided to write about Euripides’ Medea.

I love powerful women. Medea is

powerful. She is the granddaughter of Helios, the sun god.

I have been thinking about Medea for another reason. For

the last year I have been – despite good advice to the contrary – been following

the path of the civil war in Ukraine. This

line from the play has been going around my head for a while:

“Anger is frightening and hard to remedy when loved ones

join in strife with loved ones.”

What anger is more horrible than that between loved ones? An

insight such as this brings the world of 5th Century Athens very

close.

At the same time, the acts carried out by the character

Medea are so barbaric that it seems impossible that they could belong to any

conceivable time or place. But, really, I had hardly begun that last sentence

before I was struck by its naiveté. It really is nothing more than wishful

thinking to express such an idea.

Of course, overpowering rage and grotesque violence such as hers – a woman who murders her own children to exact revenge upon her husband for his infidelity – are probably not particularly uncommon. Hang around the criminal courts for a while and I am sure that Medea would soon come to seem relatively tame in comparison to some of the horrors of present day Ireland.

Of course, overpowering rage and grotesque violence such as hers – a woman who murders her own children to exact revenge upon her husband for his infidelity – are probably not particularly uncommon. Hang around the criminal courts for a while and I am sure that Medea would soon come to seem relatively tame in comparison to some of the horrors of present day Ireland.

So my first conclusion

seems to be that if its function is to

demonstrate the limits of human depravity then Medea has no particular didactic function. There isn’t much it can

teach an audience with even half an eye open!

Has Medea

therefore lost its power to shock? So much depends on the production in

question.

Lars Von Trier’s 1988 film takes the murders of the children out of the

Skene (off stage in Greek theatre) and places them in the Orchestra (right

under the audience’s noses). The scenes where Medea murders her children are

traumatising:

She, with the assistance of her older son, lifts the younger one up into the noose and drags down on his body slowly and horrifically murdering him. The older son is similarly killed. Kirsten Oleson’s acting in this film simultaneously evokes fear and pity – an Aristotelean point to which I will return – in her incredible portrayals of Medea’s rage and grief. Well, I was shocked by that production.

She, with the assistance of her older son, lifts the younger one up into the noose and drags down on his body slowly and horrifically murdering him. The older son is similarly killed. Kirsten Oleson’s acting in this film simultaneously evokes fear and pity – an Aristotelean point to which I will return – in her incredible portrayals of Medea’s rage and grief. Well, I was shocked by that production.

Medea has almost become a feminist heroine. If she is

portrayed as such then perhaps the lesson to be learned is about the lengths to

which women must go in order to oppose domination by men. Certainly, women were

not considered to be as fully human as men in 5th Century Athens. Aristotle, for example (Politics Bk 1, 1260) thought that women were by nature

subordinate; that they had an inferior capacity for both intellect and morality

and also, possessed – or were possessed by – a soul that was “without full

authority”.

Which is not to say that their importance at the foundation

of Greek society was not keenly understood.

Politically, women had their place and that was beneath men – their place

was the oikos (private space) not the

polis (public space).

In her essay "A Woman's Place in Euripedes' Medea", Margaret Williamson looks at the conflict in Medea as arising directly from the entry into the latter of someone (Medea - a woman) who does not have permission to operate there. I think this is a very useful framework to use in attempting to place this work in the history of gender - specific social change. I want to use it as a starting point to explore the didactic function of the play. It gives rise to a critical instability that opens up a space where social change can begin - it does not, however, point in any particular direction and so it throws audiences back onto their own values and ideas about how to respond to the play and the character Medea.

Economically, women were, by and large, reduced to, or

elevated to their reproductive and child – rearing capacities. This is hardly

unusual. In any society untouched by the work of feminism this oppression

passes by as people live their lives under the name of common sense or, just,

simply, nature. It is natural for women to bear and rear children. This is the foundation, the ground of any pre-modern society. When that ground begins to shake, people, especially, those in the tallest buildings

resting on those foundations start to get worried.

If Medea has a

didactic function perhaps it is to give the reminder that an earthquake could very easily bring

everything toppling down. If women start to challenge the lies that Aristotle concentrates

into a single passage in the entire work of the Politics then perhaps the lessons are only just about to start?

Of course, like any tragedy understood after Aristotle, Medea exemplifies the rule that the

tragic hero must evoke fear and pity.

“Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is

serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with

each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts

of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear

effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.”

(Poetics I VI)

What is so pitiful about Medea? She is a stranger in a

strange land, an exile, indeed, now a double exile since she’s being kicked out

of Corinth by Creon. She is a ‘barbarian’ from the modern day Caucuses; Russia,

for God’s, sorry, gods’ sakes. She has been betrayed by Jason.

Why does she evoke fear? Well, at every step she has done what women are not supposed to do. She has stepped out of the oikos and meddled, no, royally fucked shit up in the polis. Medea is an earthquake, a feminist tectonic.

Why does she evoke fear? Well, at every step she has done what women are not supposed to do. She has stepped out of the oikos and meddled, no, royally fucked shit up in the polis. Medea is an earthquake, a feminist tectonic.

And yet the purgation of fear and pity that Medea evokes is not on its own enough to really

change things. The didactic function of Medea, if it is anything, is to remind me that time

can move in any direction.

The enduring popularity of Medea proves both points: that when women refuse the private role of child rearing and child bearing and enter into the business of politics and war a blow is struck for freedom. At the same time the excess of her actions tends to provoke a reactionary ‘I told you so’ response. This is what happens when women are let out of the house.

The enduring popularity of Medea proves both points: that when women refuse the private role of child rearing and child bearing and enter into the business of politics and war a blow is struck for freedom. At the same time the excess of her actions tends to provoke a reactionary ‘I told you so’ response. This is what happens when women are let out of the house.

Greek society had specific rituals that were intended to 'allow women out of the house'; to

permit a moment of release of possibilities for women that were normally denied

by their subordinate place in the political and economic life of their world.

For example, the Thesmophoria festivals which were

women-only events that celebrated the fertility of married women. It is hard to

know if these festivals tended to reinforce the economic and political

subordination of women since they remain historically blind – only women could

participate and there are few if any surviving written accounts of what went

on. The fact that these festivals took place regularly suggests that they were

needed. In addition, the fact that they were for the wives of Athenian spouses

only suggests that they were needed at the highest levels of society.

Other festivals that were less susceptible to incorporation

in an overall structure that tended to licence their deviance were those

celebrating the god Dionysus. Dionysus is a notoriously excessive god. Although

there is no historical evidence that women went beserk, tearing animals or

humans apart (as they do in another of Euripedes’ plays The Bacchant Women) there was an amount of “Drinking, dancing and

(in Macedonia) snake handling were indeed practiced by women: sometimes they

worshipped Dionysus in ‘wild’ nature,

even up on the mountains” (R L Fox).

One way or another, the release of emotions in Dionysus’

name was not so easily controlled. Dionysus leaves a mark.

And here (remember, Dionysus is the god of dramatic tragedy

too) we can get closer to an understanding of the didactic function of Medea. Medea also leaves a mark. It is obviously fantastical to claim that

production after production of Medea over the last 2,400 years has had

a cumulative effect on western civilisation. Can I really think that the

uncontrollable excess released each time – that vision of a world where women

are not restricted to the private, the Oikos

– has had a practical effect of changing society in its own image?

I will never forget Medea.

That much is certain. What will I remember most, though: her murder of her

children to get back at her husband or her abject state as an exile, as a

sub-human woman, as betrayed by her husband, hated and loathed by all,

including herself?

Medea is both a monster and a victim. Her murder of her

children was horrific and yet, her rationale – that she “would not become a

laughing stock to [her] enemies” and that having a child was the equivalent of

going into battle three times – is typically male.

She is a woman who refuses to stay inside – she sees herself

as belonging to the polis rather than

the oikos. In killing her children

she is refusing to be consigned to the private world of child bearing and child

rearing. She is refusing to be a passive victim.

Medea is a monster but the didactic function of Medea is a reminder that monsters are

truth of history’s injustices.

Through this monstrosity Medea

teaches us that something is wrong in a world where a woman kills her

brother, her husband’s uncle, the king, his daughter and her own children.

Audiences ever since Euripides’ play came third in that year’s (431 BC) City Dionysia competition have probably

asked how can such monstrosity be avoided in reality.

This is the instability that I mentioned above. Medea is of the world beyond the play but it describes a way of living that literally destroys both the oikos and the polis. No one can live in that world because it is a world of death.

Medea leaves me with a lesson of sorts; a reminder that there is a choice. There is always a choice – either women must be kept in their (private) place or those public places into which they seek to enter have to be changed by women (and men) to accommodate women (and men).

Medea leaves me with a lesson of sorts; a reminder that there is a choice. There is always a choice – either women must be kept in their (private) place or those public places into which they seek to enter have to be changed by women (and men) to accommodate women (and men).

*Which themes do I focus on? Which themes do I thereby ignore? And what about all of the other functions of Ancient Greek Tragedy: entertainment, exhortation, propitiation of the gods? In focusing on the lessons contained within Greek Tragedy am I missing the point? And then there’s the question of which plays to choose – I mean there are, after all, only 38 surviving examples of ancient Greek tragedy so, it should be easy enough to read them all, right? Wrong. I have far too many other things to do than to read 38 Greek Tragedies! On top of all of this, there is the inescapable distance between my perspective and point in history and the world and time in which these tragedies were written and performed nearly two and half millennia ago in a language that I don’t understand. What in the world could I possibly know about the didactic intentions (if any) of Euripides, Sophocles and Aeschylus?

No comments:

Post a Comment